START WITH SCRIPTURE:

START WITH SCRIPTURE:

Luke 10:25-37

CLICK HERE TO READ SCRIPTURE ON BIBLEGATEWAY.COM

OBSERVE:

Asking questions of a rabbinical teacher was not at all uncommon. Question-and-answer dialectical method was a common style of teaching. And one of the classic questions asked of a rabbi was “what is the essence of the law, rabbi?”

However, in this case, the lawyer is also motivated by hostility to Jesus. He hoped to test Jesus’ mettle, and even to trip him up. The lawyer wasn’t a lawyer in the modern sense of an attorney — the lawyers of Jesus’ time were transcribers and interpreters of the Torah, the ancient law of Moses. They were also known as scribes.

From his question we can deduce that this lawyer is of the school of the Pharisees, who believed in the resurrection from the dead — unlike the Sadducees. He says he wants to know what he must do to inherit eternal life.

Jesus responds in a kind of Socratic manner, answering a question with a question. In this era, there was a classic question that a person might ask a rabbi — “What is the summary of the law?”

So Jesus asks the lawyer:

“What is written in the law? What do you read there?”

This suggests Jesus’ confidence in the Hebrew Scriptures of his people, that they are in fact the revealed Word of God.

The lawyer answers with appropriate Scriptures from the Law of Moses that sum up the law:

You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind.

This commandment to love God with all one’s being comes from Deuteronomy 6:5. In a sense this commandment summarizes all of the vertical commandments of a person’s relationship with God, especially as suggested in the first four commandments of the Decalogue (The Ten Commandments).

The second commandment relates to the horizontal relationships between human beings, as suggested by the last six of the Ten Commandments, and also by the ethical and social justice demands of the prophets. This commandment is also culled from the Old Testament (Leviticus 19:18b):

[love] your neighbor as yourself.

Jesus confirms that this is the way to eternal life — unreserved love for God, and unselfish love for other people:

And he said to him, “You have given the right answer; do this, and you will live.”

But remember, this lawyer has been attempting to trip up Jesus. He wasn’t sincerely seeking answers — he was seeking leverage over Jesus. So he can’t leave it alone:

wanting to justify himself, he asked Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?”

Again with questions? Jesus continues his pedagogical method of indirection. This is a form of “discovery learning.” Jesus uses parables to draw in his listeners, and then hooks them with the wisdom of his teaching.

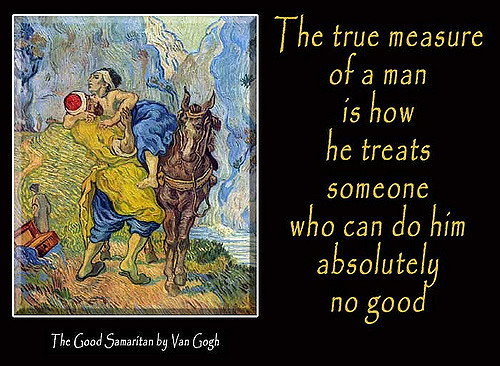

Jesus tells the famous parable of the Good Samaritan (verses 30-37).

The story is full of dramatic anticipation. The man who is journeying from Jerusalem to Jericho travels some of the most dangerous, mountainous terrain from the highlands of Judea toward the Jordan River Valley. There are plenty of hollows and gorges and caves in these mountains where a gang of thieves might hide.

The tension builds as the traveler is robbed, beaten and stripped and left for dead by just such a gang.

With keen irony, Jesus describes two men passing at different intervals on the road where the victim lies bleeding — one is a priest and the other a Levite. If anyone knew the laws of Moses, surely these men did! They should know what compassion is required for a victim, and what it means to love your neighbor! And yet they pass by on the other side. This simple phrase captures their indifference and/or revulsion for the condition of the victim.

Now comes the real twist in the story. It isn’t the priest or the Levite who fulfills the law of love — it is a Samaritan. Hostility between Jews and Samaritans goes back more than 700 years. Antipathy of the Jews for Samaritans is based on ethnic, cultural and religious differences. Pharisees regarded the Samaritans as fuel for the fires of hell simply because of their ethnicity.

And yet, it is this Samaritan, regarded as a non-person by many Jews, who has compassion for the victim. The Samaritan doesn’t ask what the ethnicity, religion or origin of the victim may be:

a Samaritan while traveling came near him; and when he saw him, he was moved with pity.

His pity is supported by action. He anoints and bandages the man’s wounds, carries him to an inn on his own animal, and pays for his care with two denarii. This would have been the equivalent of two day’s hard-earned wages for a laborer. Moreover, the Samaritan promises the innkeeper that he will pay any further bills for expenses this victim incurs.

So Jesus comes to the punchline of the story. The hook is set and the fish is caught:

Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of the robbers?

The lawyer can’t even bring himself to name the ethnicity of the Samaritan. We can imagine him answering sullenly:

“The one who showed him mercy.”

The point is clear:

Jesus said to him, “Go and do likewise.”

Eternal life begins when love for God is complete, and love for neighbor is impartial and without prejudice.

APPLY:

The lawyer asks the question that every human being who is honest with themselves will ask at some point:

what must I do to inherit eternal life?

The answer to this question in Paul’s epistles is that salvation comes through grace, received by faith in Christ’s vicarious death and resurrection on our behalf. Is this answer incompatible with the answer offered here in Luke? In the Gospels, eternal life is indeed a gift, but it is received by loving God with one’s whole self and living out that love in compassion for others.

The two views of the means of procuring eternal life aren’t incompatible at all. Faith isn’t merely intellectual assent to certain propositions. As James 2:19 reminds us:

Even the demons believe—and shudder.

It can be reasonably argued that the demons, as fallen angels, know far more about true doctrine than any human being can possibly know. But their belief is not faith.

Faith in the New Testament implies trust. And trust implies love. And if we are to truly love God — who loves all the world — then we must love all of those whom God loves. This includes even his enemies, and ours!

RESPOND:

As an ordained clergyman, this passage, though beautiful, makes me a little uncomfortable.

After all, I’m more like the priest and the Levite than I am the Samaritan in terms of my profession. The Samaritan, though unschooled in “proper” doctrine and practice, is closer to God because he loves. He expresses his love in action.

The neighbor may be defined as any person who is in need. And as Jesus tells us in Matthew 25:40, when we minister to the hungry, the sick, the stranger, the prisoner, we are actually ministering to Jesus!

Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.

True faith is love in action:

the only thing that counts is faith working through love (Galatians 5:6).

Lord, forgive me when my ‘faith’ is mere words and intellectual belief. Spur me on to love as you love— as the Samaritan loves — impartially and wholeheartedly. Amen.

PHOTOS: "The-Good-Smaritan" by Ray MacLean is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.