START WITH SCRIPTURE:

START WITH SCRIPTURE:

Mark 14:1-15:47

CLICK HERE TO READ SCRIPTURE ON BIBLEGATEWAY.COM

OBSERVE:

The climax of Mark’s Gospel approaches. The growing and intense conflict between Jesus and the religious authorities in Jerusalem reaches its culmination in the violent Passion of Jesus. Because the lectionary text for the Gospel of Mark is so lengthy, I must paint this scene with broad strokes. But in so many ways, the Passion Narrative from Mark’s Gospel speaks for itself.

It has been noted by many Biblical interpreters that when Mark’s Gospel reaches the account of the Passion, there is a distinct change of tone and pace. The first thirteen chapters of Mark move swiftly, almost breathlessly from one miracle to the next, one parable to the next. For example, Mark uses the word immediately forty-one times — far more than any other book in the Bible — denoting action. But thirty-eight of the occasions this word is used occur prior to chapter 14.

The pace slows down in Mark’s Gospel. The tone becomes darker. Mark lingers over these last few days of Jesus.

There are also contrasts here. There is an ominous sense of foreboding cast over these two chapters, as this passage begins with an introduction of the imminent feast of the Passover and the unleavened bread. The chief priests and scribes are explicit about their plot to arrest and kill him — but they are also cynical:

For they said, “Not during the feast, because there might be a riot of the people.”

But then there is the contrasting scene. Jesus is a guest at the table of Simon the leper (presumably someone that he has healed?) Perhaps this was a feast of celebration and gratitude given by Simon. And then:

a woman came having an alabaster jar of ointment of pure nard—very costly. She broke the jar, and poured it over his head.

When there is grumbling that this ointment was worth about a year’s wages for a farm worker and could have been put to use for the poor, Jesus defends her. There will be other opportunities to help the poor, but his time is short. Her deed is prophetic:

She has done what she could. She has anointed my body beforehand for the burying. Most certainly I tell you, wherever this Good News may be preached throughout the whole world, that which this woman has done will also be spoken of for a memorial of her.

Note that it is a woman who honors Jesus appropriately. In that patriarchal culture, a woman is more akin to a slave than an equal. And as we follow the narrative, note who is near when he is dying — and also who will become the first witnesses of the risen Jesus.

Now, the darkness grows deeper. There is betrayal by one of his disciples, and collusion with the religious authorities who, as we already know, seek the death of Jesus. Here there is irony. As Jesus prepares solemnly for his death, the chief priests are described as glad and offer Judas Iscariot a price for Jesus.

Then there is the occasion of the Passover, which was normally an occasion of great joy as Israel remembered their deliverance from bondage in Egypt. But this feast would be overshadowed by apprehension among the disciples, and the prescience of Jesus. He knows what is to come, which they cannot know.

There is a kind of “secret signal” — two disciples are told to follow a man carrying a pitcher of water. (Normally, carrying water was a task assigned to women.) He will lead them to an upstairs guestroom for their Passover meal. All of this seems prearranged.

And at the supper itself, Jesus casts a shadow over the occasion by predicting his betrayal — by one of his own disciples! What was normally a festive meal had certainly become depressing! Interestingly, Jesus doesn’t identify Judas Iscariot in Mark’s Gospel, leaving each of the twelve to search their own hearts, each asking:

“Surely not I?”

Jesus then transforms this historic and traditional Passover Seder into a sacrament that will be celebrated in the church until he returns:

As they were eating, Jesus took bread, and when he had blessed, he broke it, and gave to them, and said, “Take, eat. This is my body.” He took the cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave to them. They all drank of it. He said to them, “This is my blood of the new covenant, which is poured out for many. Most certainly I tell you, I will no more drink of the fruit of the vine, until that day when I drink it anew in God’s Kingdom.”

Here Jesus offers two predictions concerning his own fate — one concerning his tragic death, but the second concerning his ultimate triumph. There is bitter death signified by the bread and wine — but there is also the promise and hope of ultimate and eschatological victory. Jesus is able even now to look beyond his impending violent death toward his resurrection and eventual return.

However, the sorrow of the disciples is only begun. Jesus predicts that they will all stumble because of him that night — more specifically he quotes Scripture, from Zechariah 13:7:

‘I will strike the shepherd, and the sheep will be scattered.’

This is precisely what is about to happen. And yet once again he also foresees his own resurrection:

However, after I am raised up, I will go before you into Galilee.

Once again there is the contrast of his death and his resurrection — darkness and light.

Peter’s famous contention that he won’t leave Jesus’ side, no matter what, is met with brutal predictive honesty:

Jesus said to him, “Most certainly I tell you, that you today, even this night, before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me three times.”

We note that all of the disciples made the same protest that Peter did — that they would die with Jesus before they denied him. But of course Jesus would be proven correct by subsequent events.

The picture we have is that Jesus is wrestling with nearly everyone, including the priests and even his own disciples. Only the woman who anoints his head with oil at the beginning of the scene seems to intuitively understand him. The disciples, who have spent so much time with him over the previous short years, still don’t get it.

And on the Mount of Olives, in the place called Gethsemane, this struggle comes to a head. (Gethsemane means olive press, because that’s where the olives were crushed into oil. How appropriate for the one whose body was to be broken and poured out!).

The three closest disciples (Peter, James, and John) can’t even stay awake while Jesus prays, even though he has told them how troubled he is. All of the disciples have been charged to pray for him. Yet he is alone with the Father.

It might be said that this moment in the Garden is the climax of his struggle, and that he is perhaps even wrestling with God the Father. But we note that he addresses his Father as Abba. Many scholars suggest that this is the familiar and intimate term of endearment that a child might call his father, like “daddy.”

But we see also that despite his preference that he not endure the cross, Jesus surrenders his will to the purpose for which he has come:

He went forward a little, and fell on the ground, and prayed that, if it were possible, the hour might pass away from him. He said, “Abba, Father, all things are possible to you. Please remove this cup from me. However, not what I desire, but what you desire.”

There is a pattern of threes in this passage. Jesus tells Peter he will deny him three times. Jesus finds his disciples sleeping three times. He is on his own. He says of them:

The spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak.

The third time it is too late for them to pray. Jesus senses that Judas and the mob are coming. We marvel at the hypocrisy of Judas Iscariot, who says to the chief priests, scribes and elders that he will identify Jesus with a kiss, and then calls out to Jesus with the honorific title “Rabbi! Rabbi!”

Jesus knows that this stealthy, shameful arrest by night is an act of cowardice on the part of the religious leaders:

Have you come out, as against a robber, with swords and clubs to seize me? I was daily with you in the temple teaching, and you didn’t arrest me. But this is so that the Scriptures might be fulfilled.

There is some violent resistance by one of the disciples, but it is brief. After one cuts off a servant’s ear, the disciples all flee into the night. Their escape is so panicked that one of the young men’s loose robe is torn from him by those seeking to arrest him, and he flees into the darkness. Some early commentators speculated that because this detail is unique to Mark’s Gospel that the young man was John Mark, the writer of the Gospel of Mark himself. We just don’t know for sure.

Somehow, despite the terror of the arrest, Peter follows the procession of this mob to the court of the high priest — from a safe distance.

Again, there is a fascinating contrast — two trials, if you will. Jesus is on trial for his life before the council — the Sanhedrin. Meanwhile, Peter’s integrity and loyalty are on trial in the courtyard while he warms himself by the fire.

The accusations made against Jesus are false and contradictory. No legitimate court could convict based on spurious testimony. However, it is the words of Jesus himself that seal his fate:

Again the high priest asked him, “Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed?”

Jesus said, “I am. You will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of Power, and coming with the clouds of the sky.”

From the perspective of the high priest and the members of the council, this is blasphemy and heresy. The description that Jesus offers of himself is apocalyptic and Messianic. When he calls himself the Son of Man he is alluding to the Old Testament prophecies of the Messiah. But surely it cannot have been lost on some of these Hebrew scholars that when Jesus says I am, that phrase evokes the holy name of Yahweh from Exodus 3! Not only is he claiming to be Son of Man, but he is also claiming to be Son of God!

The consequences are dire. The high priest tears his clothes, which is a sign of deep mourning — but the high priest was never to tear his robe, according to the law (see Leviticus 21:10). This suggests the intensity of the priest’s reaction to the words of Jesus.

Then there is the beginning of the brutal violence and contemptuous humiliation that rains down upon Jesus. This will not stop with these council members and officers of the temple guard. He will be abused also by the Roman legionnaires. As prophesied in Scripture, Jesus would be beaten, spat upon, lashed, mocked — all prior to his actual execution.

Meanwhile, Peter’s “trial” was also reaching a climax. A maid accuses him of being with the Nazarene and then begins to harangue him to others nearby — presumably so that some of the officers might arrest him. Peter fails the test but fulfills the prophecy of Jesus. Before the rooster crows twice, Peter has denied Jesus three times, finally becoming quite vehement:

he began to curse, and to swear, “I don’t know this man of whom you speak!” The rooster crowed the second time. Peter remembered the word, how that Jesus said to him, “Before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me three times.” When he thought about that, he wept.

Because Israel (known as Judea in Palestine at that time) was under Roman authority, there was a clear division of powers. The Jewish religious authorities could manage their religious affairs, but only under the close supervision of Rome. Therefore it was necessary to seek a civil judgment against Jesus.

When the night is over, Jesus is hailed before Procurator Pilate. Pilate’s question does not relate to any religious significance of the claims of Jesus. He is concerned with only one thing:

Pilate asked him, “Are you the King of the Jews?”

The implications are clear. Pilate must find a political pretext to execute this prisoner. Religion is irrelevant, since the Jews had a special dispensation from Rome to preserve their own religious traditions. But a king who might raise a rebellion against Rome? That’s another matter.

Jesus won’t satisfy Pilate with an answer, except an enigmatic one:

He answered, “So you say.”

Pilate’s attempt to find an escape clause to this dilemma backfires. When he offers the people a choice between Jesus and Barabbas, they choose Barabbas. This is a disaster for Pilate. As far as he is concerned, Jesus is merely a religious fanatic who gathered a crowd in the countryside. But Barabbas was the modern-day equivalent of a political terrorist:

There was one called Barabbas, bound with his fellow insurgents, men who in the insurrection had committed murder.

He, and the two men who were to be crucified with Jesus, may well have been Zealots who advocated a violent uprising and overthrow of their Roman occupiers.

It is important to remember that the cross was a form of execution normally reserved for sedition or treason — like the violent insurgents who had committed murder — or a man who claimed to be a king. This is why, when the Roman soldiers mock Jesus with a purple robe of royalty, and press a crown of thorns onto his head, they hailed him as King of the Jews. That mockery, and the cross itself, was a sign to the population of Jerusalem — “this is what Rome does to royal pretenders. The only true power here is Rome.”

Flogged, beaten, sleepless, Jesus carries his cross to Golgotha. Mark doesn’t tell us that Jesus falls, or is too weak to carry the cross because of a loss of blood. Floggings were often a death sentence in themselves.

The soldiers command a foreigner in the crowd to carry his cross. His name is given — Simon of Cyrene. Again, this is a fascinating detail. Cyrene was a Greek and Roman city in modern day Libya — North Africa! This doesn’t suggest that Simon was a Gentile — there were Jewish settlers in Egypt as well as all over the ancient world in the Mediterranean area and the Near East. And it would not have been unusual for a Jew to make the pilgrimage to Jerusalem for the Passover — especially bringing his sons.

And the mention of his sons, Alexander and Rufus, is also fascinating. Mark seems to assume that they are known to his readers. Some scholars speculate that they became a part of the Christian community after witnessing the horrors of the cross. The names Alexander and Rufus do appear in some of the Epistles.

It was at 9:00 a.m. that they arrived at the very public hill of execution called Golgotha (that is, the place of the skull). Again, we are reminded that this execution is a public example, and a deterrent to would-be insurrectionists. The charge against Jesus, inscribed above his head, made this clear:

THE KING OF THE JEWS.

Our translation says that the other two crucified with him were robbers, but other translators suggest that they were actually Jewish rebels or insurgents, arrested with Barabbas after the recent riots in Jerusalem. Again, Mark spots the fulfillment of Scripture, this time from Isaiah 53:12:

“He was numbered with transgressors.”

This reference to Isaiah 53 points to the famous passage describing the Suffering Servant, which the church has come to see as a vivid picture of Jesus as the Messiah who suffers vicariously for all sinners.

Now Jesus is completely abandoned — almost. In Mark’s Gospel, people passing by on the road taunt him. The chief priests and scribes demean their own dignity and mock him. And in Mark’s Gospel, both of those crucified with him also insult him. And after darkness falls on the face of the earth (from about noon to three o’clock), it seems that Jesus feels abandoned even by his God, quoting Psalm 22:

At the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, saying, “Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani?” which is, being interpreted, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

The taunts of the spectators, and the only words uttered by Jesus on the cross in Mark’s Gospel, are a little problematical. The mockers are actually on the right track. Jesus did promise to rebuild the temple, but in their wooden literalism they fail to understand he spoke of his own resurrection — which would occur in three days. And in a paradoxical sense, when the religious authorities said “He saved others. He can’t save himself,” they were correct. If he saved himself by coming down from the cross, he would be unable to save others. By losing his life, he saves billions upon billions.

And when Jesus cried out to God, was it truly a cry of desolation or a prayer of hope? (For a more complete treatment of this dilemma, please see: https://soarlectionarybiblestudy.wordpress.com/2017/04/06/gospel-for-april-9-2017-liturgy-of-the-passion/). We are reminded that Jesus is dying slowly of asphyxiation on the cross. He hasn’t the breath to recite all of Psalm 22, which seems clearly to describe the effects of a suffering victim, with eerie similarity to a crucifixion. He certainly can’t hold out until the verses near the end of the Psalm, that ring with hope:

You who fear Yahweh, praise him!

All you descendants of Jacob, glorify him!

Stand in awe of him, all you descendants of Israel!For he has not despised nor abhorred the affliction of the afflicted,

Neither has he hidden his face from him;

but when he cried to him, he heard (Psalm 22:23-24).

Typically, Jesus is misunderstood by those standing nearby. They think he is calling Elijah to rescue him.

The only other utterance from Jesus seems to be a cry of either agony — or triumph:

Jesus cried out with a loud voice, and gave up the spirit.

We are told that the veil of the temple was torn in half, from top to bottom. The veil in the temple was not a mere sheer curtain. According to the ancient historian Josephus, the veil in Herod’s temple was as thick as a man’s hand (about four inches thick) and 60 feet high and 20 feet wide.

This is the veil that separated the Holy Place in the temple from the innermost room known as the Holy of Holies. The Holy Place was the location of solemn worship where only the priests were permitted to go. The following items were in the Holy Place — the table for the showbread, the altar of incense which represented the prayers of Israel, and the seven-branched lampstand that offered light for the room. These were all articles carefully prescribed by Yahweh to Moses in the book of Exodus.

However, the Holy of Holies was the most holy place, where the high priest entered only once a year on the Day of Atonement to offer sacrifices for the sins of Israel. The significance of the tearing of the veil is clear — Jesus the true high priest has opened the way into the presence of God.

Perhaps a massive earthquake, such as was described in Matthew 27:54, might have caused such a rupture. No wonder the Roman centurion said:

“Truly this man was the Son of God!”

Perhaps there were a combination of factors that contributed to this startling confession of faith by a Gentile. The natural phenomenon must have moved him — the deep darkness over the land for three hours, the earthquake. Or perhaps there was something he saw and felt as he watched the Son of God die.

Earlier, I wrote that everyone seemed to have rejected or abandoned Jesus — the spectators, the religious authorities, and some would say even God (although I disagree. See Respond section below). But there were some who did not:

There were also women watching from afar, among whom were both Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James the less and of Joses, and Salome; who, when he was in Galilee, followed him, and served him; and many other women who came up with him to Jerusalem.

These are the same three women mentioned by name who will bring spices to anoint his dead body after Jesus is placed in the tomb — and the same women who are the first witnesses to the resurrection.

And ironically, it is not one of his closest disciples who has the courage to ask Pilate for the body of Jesus on Preparation Day, the day before Sabbath. We may presume they are still in hiding. No, it is Joseph of Arimathaea, a member of the same Sanhedrin that condemned Jesus:

who also himself was looking for God’s Kingdom.

Obviously, like the centurion, Joseph of Arimathaea saw something in Jesus that had deeply reached him.

Pilate seems surprised that Jesus is already dead:

Pilate marveled if he were already dead; and summoning the centurion, he asked him whether he had been dead long.

Jesus is wound in a linen cloth and laid in a tomb cave. Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of Joses note where he has been buried. They plan to return when the Sabbath is over and anoint his corpse.

APPLY:

Just who is this Jesus, and what is our response to him, and to his violent death?

To the chief priests and scribes, and the religious elite of the day, Jesus was a heretic who needed to be eliminated before he corrupted their precious temple worship, and perhaps incurred the wrath of Rome for stirring up trouble.

To the disciples, he was their beloved Rabbi, their Teacher, who had taught them of the Kingdom of God, and then had demonstrated its presence with his powerful signs. But when he spoke of his own death and resurrection, they couldn’t understand him. Not yet.

To Pilate, and the Roman overlords, he was a political problem to be solved. What happened to Jesus was a matter of indifference. If he could be released without consequences, that would be fine. If not, he could be crucified as a matter of convenience to appease the priests and avoid trouble with Rome.

To the women who had been treated as equals and human beings of sacred worth for the first time in their lives, he was Lord — and they demonstrated their reverence by anointing his head with oil, and watching in grief as he died.

To Joseph of Arimathaea — well, we’re not sure what he thought of Jesus. We simply know what he did. As in the deuterocanonical (or Apocryphal) book of Tobit, he perhaps saw the burial of a fellow Jew as a sacred duty. But we suspect that it meant much more than that. He was looking for the kingdom, and perhaps he’d caught a glimpse of the kingdom in the eyes of the King.

But most importantly, what is he to us? Many today dismiss Jesus as a non-historical character invented by men to support a corrupt institution. Some think of him as a fine moral character whose teachings were part of the ethical development and evolution of our civilization.

That is too easy. Many of us find ourselves reading the Passion account and determine, as many Christians have over the centuries, that these details are too vivid and too realistic to be fiction. They have the feel of truth.

And perhaps we find ourselves in the same position as the centurion. We doubt that he had much contact with Jesus prior to this execution. But there is something here that grips him, that speaks to his spirit, and that causes him to declare:

“Truly this man was the Son of God!”

It is interesting that in the Gospel of Mark, Jesus never calls himself the Son of God. This is the title given Jesus by Mark in the beginning of the book:

The beginning of the Good News of Jesus Christ, the Son of God (Mark 1:1).

And the unclean spirits recognize him for who he is as the Son of God. But Jesus invariably refers to himself as the Son of Man. Perhaps this is because he is stressing his human nature, and his role as the Messianic figure of prophecy. He knows that he is the Son of God.

However, it is when we recognize that he is the Son of God that we truly come to faith. And it is then that we know that God has become one of us, with all the weakness and vulnerability that is revealed on the cross, so that he might demonstrate his power as the crucified and risen God.

RESPOND:

I sometimes read history and wonder, “What would I have done?” Would I have stood my ground when the Redcoats charged up Breed’s Hill in Boston? Would I have spoken up against Hitler in Nazi Germany? But more importantly, would I have stayed close to Jesus that night when he was arrested?

I’d like to think that I would have remained near him, like the women did. Of course, the Roman legionnaires and the religious authorities likely took no notice of the mourning women. In that culture long ago, women were of little consequence.

But the sorry record of the male disciples makes me doubt myself. If Peter, James and John ran, or kept their distance, or even denied him, do I really think I would do any better?

They did forsake him. But here’s another pressing question — Did the Father forsake his Son? This is a theological conundrum.

I have heard sermons over the years that insisted that when Jesus was on the cross, the Father “turned his face away from his Son.” I understand where they’re coming from. When Jesus quotes Psalm 22 it does seem to be a cry of abandonment. And Paul tells us that:

For him who knew no sin he made to be sin on our behalf; so that in him we might become the righteousness of God (2 Corinthians 5:21).

I am not troubled by the fact that Jesus assumes my sin in order to transfer his righteousness to me. This is the purpose of the sacrifice — an exchange of sin for righteousness. Jesus does not commit sin (we know from Scripture that he is without sin — see 2 Corinthians 5:21; Hebrews 4:15), but he assumes our sin. Only one who is fully divine is without sin. And only one who is fully human can fully enter into our human experience and take our sin upon himself.

And that’s what troubles me.

Jesus is so clearly established in the New Testament as the only begotten Son of the Father, the Word made flesh. He is God. Not merely God-like, but God. His own claim is that he is uniquely united to the Father:

I and the Father are one (John 10:30).

And he decisively answers Philip’s request that the disciples may see the Father:

He who has seen me has seen the Father. How do you say, ‘Show us the Father?’ Don’t you believe that I am in the Father, and the Father in me? (John 14:9-10).

This is the basis of the classic doctrine of the nature of Jesus as fully God and yet fully man, as understood by the church. And it is the basis of the Trinity, that Jesus is the Second Person of the Trinity.

How then could God the Father abandon himself? It seems to be ontologically impossible. Though there is a distinction of Persons in the Trinity, there is still complete unity between Father, Son and Holy Spirit. This explains my difficulty with the theory that “the Father turned his face away from his Son.”

I heard about a little girl who said “I love Jesus, but I hate his Father.” In her innocence, I believe she missed the point. It is not the Father who crucifies the Son — it is evil itself, manifested in human sin.

Therefore I can come to only one conclusion — the Father didn’t turn his face away from his Son. There may be a hint of this in Luke’s account of the last moments of Jesus:

Jesus, crying with a loud voice, said, “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit!” Having said this, he breathed his last (Luke 24:46).

On the cross God the Father embraces his Son, as the one who has been perfectly obedient even unto death. The Father doesn’t watch this horror from a distance — he is as near to the suffering Son as he has ever been, watching with deep love. Grieving, mourning perhaps because of what human evil had done — but absent? Never.

In the words of Charles Wesley’s powerful hymn, Arise, My Soul, Arise:

The Father hears Him pray,

His dear anointed One;

He cannot turn away

The presence of His Son.

His Spirit answers to the blood,

And tells me I am born of God.

It is the God-Man who dies on our behalf, who tastes the worst that evil can deliver (even, according to ancient church doctrine and Scripture, descending into Hell itself), and then is raised to life by God. This descent and ascent is no mere myth. Jesus has descended to rescue us from sin, death and the Devil, and has re-ascended with us in his arms. As Ephesians 4 tells us:

“When he ascended on high, he led captivity captive, and gave gifts to men.” Now this, “He ascended”, what is it but that he also first descended into the lower parts of the earth? He who descended is the one who also ascended far above all the heavens, that he might fill all things (Ephesians 4:8-10).

So, forsaken by all but God, because Jesus is God incarnate, Jesus sets free the prisoners from their dungeon. Thanks be to God who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ!

Lord, I confess I have said and written too much about a mystery that I cannot begin to understand — your Passion, death and Resurrection, your ineffable nature, the Trinity. Please forgive what I have said amiss; but lead me again to the same confession made by the centurion at the foot of the cross: “Truly this man was the Son of God!” Amen.

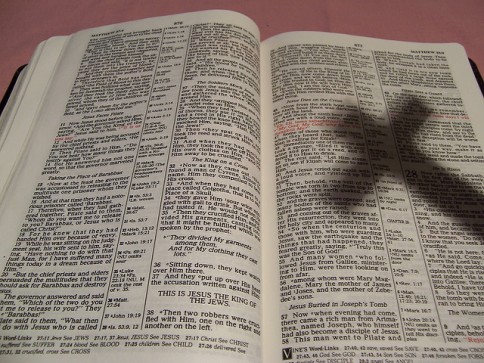

PHOTO:

“It is Finished!” by Delirious? is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license.