START WITH SCRIPTURE:

START WITH SCRIPTURE:

Micah 6:1-8

CLICK HERE TO READ SCRIPTURE ON BIBLEGATEWAY.COM

OBSERVE:

The prophet Micah was a contemporary of Isaiah. In fact, some of his language and imagery closely parallels the language of Isaiah. Micah reveals his context at the beginning of his oracles:

Yahweh’s word that came to Micah the Morashtite in the days of Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, kings of Judah, which he saw concerning Samaria and Jerusalem (Micah 1:1).

This era would have covered the years 742 to 686 B.C. Micah himself was from Morasheth in Judah which was near the border of Philistia, about 25 miles from Jerusalem.

He was prophesying to both the Northern Kingdom of Israel (aka Samaria) and the Southern Kingdom of Judah in a time of deep anxiety. In 735 B.C., King Rezin of Syria and King Pekah of Israel formed an alliance against King Ahaz of Judah and besieged Jerusalem. Other nations, such as Philistia and Edo, were taking advantage of Judah’s vulnerability. A desperate Ahaz appealed to King Tiglath-Pileser of Assyria for help.

The Assyrian king did “help” — he helped himself to Syria and to part of the Northern Kingdom known as Galilee. Then in 721 B.C., another Assyrian king known as Sargon conquered Israel/Samaria and deported its people from their land. And then the Assyrians under Sennacherib’s leadership began a campaign against Judah, capturing cities in this remaining kingdom, and besieging Jerusalem itself in 701 B.C.

Much of Micah’s prophetic career and writing were intended to warn Israel and Judah that they must repent and turn from idolatry and social injustice, and turn back to Yahweh.

This is the context of this week’s lectionary text for the Old Testament. In Micah 6, Yahweh is summoning his people to a kind of court hearing, demanding that they plead their case in the presence of the mountains which surround them. Yahweh has a grievance against his people, and he asks them:

My people, what have I done to you?

How have I burdened you?

Answer me!

Then Yahweh reminds his people of all that he has done for them — he has delivered them from bondage in Egypt; he sent great leaders to guide them — Moses, Aaron and Miriam — who were the epitome of greatness and devotion to Yahweh. These two brothers and their sister led Israel from Egypt, through the wilderness, and provided the framework for Israel’s law and worship.

Micah also alludes to an encounter that occurred during those early years of Israel’s history, when Israel was drawing closer to the Promised Land of Canaan during their wandering in the wilderness. Yahweh says:

My people, remember now what Balak king of Moab devised,

and what Balaam the son of Beor answered him from Shittim to Gilgal,

that you may know the righteous acts of Yahweh.

This is a reference to events recorded in the book of Numbers, when Israel was preparing to enter Canaan from the east. They were required to travel through the region of Moab, and Balak was apprehensive because Israel had already defeated the Amorites in battle. So Balak sought out a Moabite prophet named Balaam, and tried to bribe him to curse the Israelites. But Yahweh instead put words of blessing in Balaam’s mouth instead of cursing (cf. Numbers 22-24).

The reference to Shittim and Gilgal are geographical reminders of Yahweh’s providential care of Israel — Shittim was the final encampment of the Israelites east of the Jordan river, and Gilgal was their first camp on the west bank of the river. This was a shorthand way of saying that Yahweh had guided his people all the way from Egypt, through the wilderness, and in the transition to the promised land.

So, rhetorically, Yahweh is asking Israel — which of these blessings that I have provided for you are you unhappy with? Obviously, the answer should be — none of them!

So, Micah begins to answer Yahweh on behalf of Israel. He does this through a series of rhetorical questions:

How shall I come before Yahweh,

and bow myself before the exalted God?

Micah’s questions begin reasonably enough, but soon become preposterously exaggerated and even horrible:

Shall I come before him with burnt offerings,

with calves a year old?

Will Yahweh be pleased with thousands of rams?

With tens of thousands of rivers of oil?

Shall I give my firstborn for my disobedience?

The fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?

His last question is obviously outrageous — Micah knows that human sacrifice is a feature of the worship of the Canaanite god Molech, and is expressly forbidden in the Law (cf. Leviticus 20:1-5).

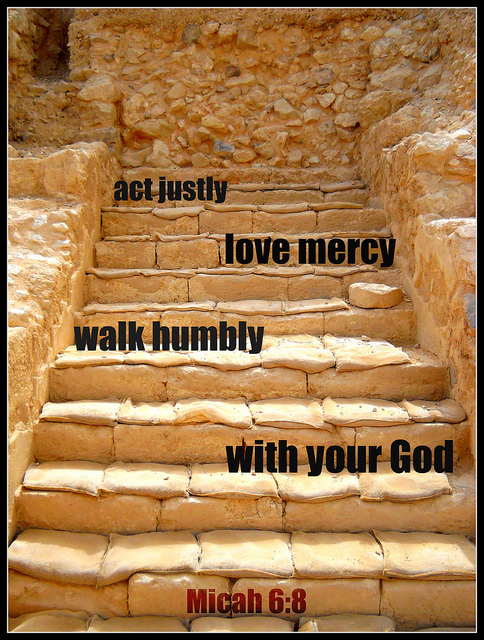

And then Micah answers his own question by summing up what Yahweh requires. Essentially, he suggests none of the above. Instead, Micah says God has made clear what he wants from his people:

He has shown you, O man, what is good.

What does Yahweh require of you, but to act justly,

to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God?

This triad of requirements sums up the ethical and spiritual values of the Mosaic Law and the prophets — justice and mercy cover human relations and how human beings are to treat one another. To walk humbly with God suggests a personal relationship with Yahweh — we note that Micah doesn’t mention temple sacrifices, except in a somewhat satirical fashion as mentioned above. Walking humbly with God is more than ritual observance — it is relationship.

APPLY:

This passage presents one of the most famous passages in Scripture:

He has shown you, O man, what is good.

What does Yahweh require of you, but to act justly,

to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God?

First, though, we must remember that our ethical and spiritual response is grounded not in what we do, but in what God has done. Micah has made it clear that Yahweh is the redeemer and deliverer of his people by reminding them of their liberation from slavery in Egypt, and his fulfillment of his promise to lead them into the Promised Land. This is a reminder to us as Christians that we are the recipients of God’s grace. We must never lose sight that the heart of the Biblical message is what God has done for us, not what we have done for God or ourselves.

Second, there is the summary of the response required from us. It is simple, but not necessarily easy — a little like Jesus’ summary of Old Testament Law:

‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the first and great commandment. A second likewise is this, ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ The whole law and the prophets depend on these two commandments (Matthew 22:37-40).

These “Great Commandments” provide a picture of our vertical and horizontal requirements — vertical requirements cover our relationship with God, and the horizontal requirements cover our relationship with other people. The key word is “relationship.” Love for God and neighbor (and yes, even for enemy) are not abstract, but relational.

Micah’s summary is also relational.

- Justice has to do with treating others fairly, impartially and equally — corporately and individually.

- Mercy has to do with compassion, feeding the poor, helping the helpless, caring for the sick and the vulnerable.

- Walking humbly with God is about cultivating a personal relationship with God — not excluding public worship but also including personal prayer and dependence on God on a daily basis.

In these three simple requirements we may find a wide application to our lives in terms of social justice, care for the environment, comfort and care for the sick, the poor, the hungry; all grounded in our deep relationship with God.

RESPOND:

One of my favorite pastimes is walking. My wife and I walk five or six days a week, if at all possible, and we prefer to walk in one of our state parks, sometimes for two or three hours at a time.

I have found this to be one of my primary means of grace. During these walks in the woods especially, my wife and I are usually very quiet, alone with our own thoughts. These are times of deep prayer for me, and often times when insights come through most clearly.

So, I resonate with Micah’s language about doing justice, loving mercy, and walking humbly with our God. It doesn’t take long to figure out that this metaphor of walking with God is deeply embedded in the Biblical lifestyle. Many of the great figures of Scripture are described as people who walked with God.

- Enoch, Abraham, Isaac (cf. Genesis 5:24; 17:1; 48:15).

- Moses appeals to the Israelites to walk in the law of God (cf. Exodus 18:20).

- Jesus declares that those who follow him will walk in the light (cf. John 8:12).

- Paul tells the Galatians that they are to walk in the Spirit, with the fruits of the Spirit that will result (cf. Galatians 5:16).

I pray that I will continue to walk with God in such a way in my daily life that I reflect God’s justice, mercy and love every day.

Lord, I am grateful first of all for the grace that you have poured out in my life through the death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus, and that you continue to pour out in my life through your Holy Spirit. I pray that you will empower me to treat others with justice and mercy, and to walk humbly with you all the days of my life. Amen.

PHOTOS:

“WFW Micah 6:8” by chelled is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license.