START WITH SCRIPTURE:

START WITH SCRIPTURE:

Romans 8:12-25

CLICK HERE TO READ SCRIPTURE ON BIBLEGATEWAY.COM

OBSERVE:

The Apostle Paul continues his line of thinking concerning the new life of those who are in Christ Jesus and walk according to the Spirit.

He returns to language he has used earlier, contrasting the life of the flesh to the life of the Spirit. He declares that those who live according to the Spirit are not indebted to the flesh, nor required to live according to its demands. This is a financial metaphor that suggests the cancellation of any obligation to the flesh. We are reminded that Paul’s definition of the flesh includes those affections, attachments and cravings that lead one away from God and toward sin and death:

For the mind of the flesh is death, but the mind of the Spirit is life and peace; because the mind of the flesh is hostile towards God; for it is not subject to God’s law, neither indeed can it be. Those who are in the flesh can’t please God (Romans 8:6-8).

He then articulates a rhetorical paradox:

For if you live after the flesh, you must die; but if by the Spirit you put to death the deeds of the body, you will live.

To ‘live’ after the flesh is to die; to die to the flesh (which means repudiating a lifestyle of moral corruption and decay that leads to death) brings life! The paradox couldn’t be more radical — living after the flesh brings death; dying through the Spirit brings life. This has been foreshadowed in Romans 6 when Paul speaks of being baptized into Jesus’ death:

We were buried therefore with him through baptism to death, that just as Christ was raised from the dead through the glory of the Father, so we also might walk in newness of life (Romans 6:4).

Having established this principle, that dying to the flesh through Christ and being raised with him through the power of the Spirit brings new life, Paul introduces another mind-blowing concept — that those who belong to the Spirit are no longer in bondage, but are children of God!

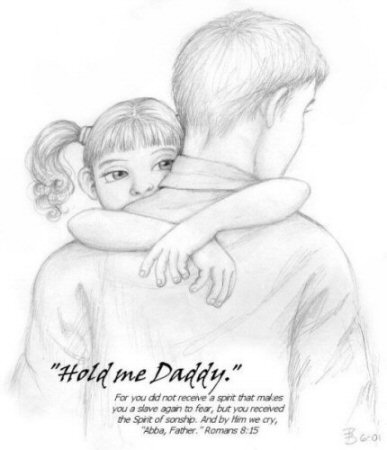

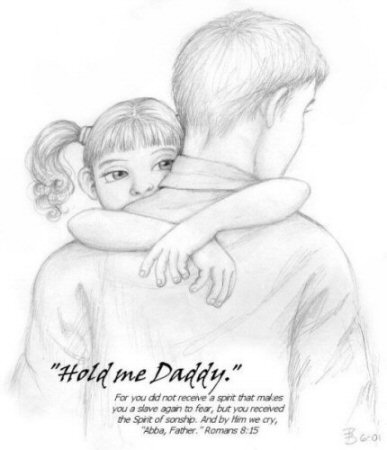

For as many as are led by the Spirit of God, these are children of God. For you didn’t receive the spirit of bondage again to fear, but you received the Spirit of adoption, by whom we cry, “Abba! Father!”

Note the important statement Paul makes. The Christian is no longer in bondage, but is adopted as a child of God. We must be quite clear — though we were all created by God and loved by God, even while we were yet sinners (cf. Romans 5:8), it is through the witness of the Spirit that we become God’s adopted children. It might be said that God has only one begotten Son, who is Jesus (cf. John 1:14, 18; 3:16); all the rest who are his children are adopted for the sake of Jesus and his sacrificial fulfillment of the law, and claimed as family through the testimony of the Spirit.

This new family relationship is strongly emphasized by the permission granted to these new children that they may call God “Abba! Father!”

Modern scholars debate the Aramaic title Abba — whether it means Daddy or more formally, Father. In any case, it does seem to denote an intimate, even affectionate, relationship between a father and child. Jesus uses this term one time that we are aware of — when he is praying to his Father in the Garden of Gethsemane (the night of his arrest, which leads to his death). Mark’s Gospel describes the scene:

He went forward a little, and fell on the ground, and prayed that, if it were possible, the hour might pass away from him. He said, “Abba, Father, all things are possible to you. Please remove this cup from me. However, not what I desire, but what you desire.” (Mark 14:35-36)

Paul uses the term Abba again in a passage from his letter to the Galatians that closely parallels Romans 8:14-17:

But when the fullness of the time came, God sent out his Son, born to a woman, born under the law, that he might redeem those who were under the law, that we might receive the adoption of children. And because you are children, God sent out the Spirit of his Son into your hearts, crying, “Abba, Father!” So you are no longer a bondservant, but a son; and if a son, then an heir of God through Christ (Galatians 4:4-7).

The point is, those who are now in Christ are adopted as children of God in a new and intimate relationship. In fact, this last claim is what Paul says in the next few verses:

The Spirit himself testifies with our spirit that we are children of God; and if children, then heirs; heirs of God, and joint heirs with Christ; if indeed we suffer with him, that we may also be glorified with him.

The Christian knows that he or she belongs to God because the Spirit has told them so in their own spirit. And as joint heirs with Christ, the Christian inherits whatever Christ inherits as the only Son of God — the believer is made brother and sister with Christ himself!

Paul does have one caveat, however. There is an if involved with this adoption:

if indeed we suffer with him, that we may also be glorified with him.

Paul’s understanding of baptism and faith is not that baptism is a mere “symbol” and faith merely “belief” that certain facts are true. To become a Christian through baptism and faith is to be identified with Christ and his sufferings. Paul says this very clearly earlier in this letter:

For if we have become united with him in the likeness of his death, we will also be part of his resurrection; knowing this, that our old man was crucified with him, that the body of sin might be done away with, so that we would no longer be in bondage to sin (Romans 6:5-6).

We must bear in mind that there is the symbolic identification with the death of Christ in baptism — but suffering with Christ in order to be glorified with him may in Paul’s mind be quite literal. He writes to a persecuted church, which knew what it was to experience discrimination, insult, and even violence. (Those of us in the Western church may not be able to appreciate this in quite the same way as those in the parts of the contemporary church throughout the world where suffering with Christ is no figure of speech).

However, Paul also declares that any suffering experienced in this life is more than transcended by God’s promises to his children:

For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory which will be revealed toward us.

Here is another dramatic contrast — between the sufferings of the present, and the glories of the Kingdom of God that is to come. There is no comparison.

Still, there is a provisional nature to the Christian’s life in the present — the “not yet” of one’s life in Christ.

Paul expands his focus concerning the present and the future. He claims that even creation itself is anticipating the eschatological age to come:

For the creation waits with eager expectation for the children of God to be revealed.

Paul personifies creation as a being with emotions — it is subjected to vanity, the bondage to decay, and even groans and travails in pain. Although Paul doesn’t spell it out, he appears to be basing his creation theology on the concept that creation itself has been infected by the same sin and evil with which humans have been infected. We can’t help but think of the language of Genesis when Adam and Eve experience the consequences of their disobedience — even the earth is cursed!

…the ground is cursed for your sake.

You will eat from it with much labor all the days of your life.

It will yield thorns and thistles to you (Genesis 3:17-18).

Creation is not to blame for this curse — humanity is. Nevertheless, God will use this curse in order to bring good out of evil:

For the creation was subjected to vanity, not of its own will, but because of him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself also will be delivered from the bondage of decay into the liberty of the glory of the children of God.

Therefore, the wonderful promise of the coming age is that not only will the children of God be delivered from the bondage to sin and death, creation itself will be delivered from decay and liberated to become what God intended at the beginning!

Creation groans because of its bondage to decay as it leans hopefully toward the coming age, and so do those who belong to Christ:

Not only so, but ourselves also, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, waiting for adoption, the redemption of our body.

Note that Paul is decidedly speaking of the “not yet” aspect of the coming of the end.

There are the first fruits of the Spirit that have already been given “now” to the believer. Paul doesn’t spell out exactly what those first fruits are in this passage. Sometimes he uses this phrase to describe Christ’s own resurrection, that has already taken place:

But now Christ has been raised from the dead. He became the first fruits of those who are asleep (1 Corinthians 15:20).

The concept of first fruits is grounded in the Mosaic law governing gifts offered to God (cf. Exodus 23:16, 19) from the agricultural yields of the fields and the flocks. These were the first tokens, symbolizing the giving of the best to God. And secondly, the first fruits were offered as a reminder that all things ultimately belong to God.

But the first fruits in our passage no doubt are related to the foretaste given to the believer through the Spirit, as suggested elsewhere:

Now he who establishes us with you in Christ, and anointed us, is God; who also sealed us, and gave us the down payment of the Spirit in our hearts (2 Corinthians 1:21-22).

And Paul may also have in mind those qualities of character that are bestowed by the Spirit even now:

the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faith, gentleness, and self-control (Galatians 5:22-23).

However, they are still awaiting the fullness of salvation that comes at the end of the age. In fact, as he has said, believers have been adopted as children of God — and yet that adoption is not yet fully complete until the end of the age. And though believers have been redeemed by Christ’s blood, the full redemption of their bodies from the decay of this life isn’t completed until the end of the age either.

So Paul is obliged to speak of hope, not as something which has been completely fulfilled, but what is yet to be:

For we were saved in hope, but hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for that which he sees? But if we hope for that which we don’t see, we wait for it with patience.

APPLY:

This excerpt from Romans 8 has far-reaching implications — some might even say cosmic implications!

First, though, the impact of this passage is deeply personal and intimate. Those who have been in bondage to the flesh and to fear are set free through the Spirit of God.

But wait (as they say in the advertising world), there’s more! The unimaginable has been made possible — through the Spirit of God, we are adopted as children of God. This is made possible by what Christ has done for us, as Paul explains in Galatians:

But when the fullness of the time came, God sent out his Son, born to a woman, born under the law, that he might redeem those who were under the law, that we might receive the adoption of children (Galatians 4:4-5).

Our adoption as children of God is clearly grounded in the incarnation event of Christ and fulfilled in his death and resurrection.

And it is the Holy Spirit who completes this “contract” of adoption by witnessing inwardly to our spirits that we are children of God. To be adopted into this family is to have all that Jesus has in his relationship with the Father! We are on such intimate terms with God that we can talk to him as Abba — Daddy.

And if Jesus inherits a new, resurrection body, so do we! If Jesus inherits eternal life, so do we! If Jesus inherits the right to sit in the heavenly places with the Father, so do we (cf. Ephesians 2:6). According to Paul’s words, that we are joint heirs with Christ, we receive what Christ receives!

However, there is also the sense that, as the old cliche said, “If you can’t bear the cross, then you can’t wear the crown.” We also are to suffer with him. Obviously, Jesus has borne the cross on our behalf — we aren’t crucified for our own sins. Jesus has paid that penalty for us. Still, we are to identify with Jesus through our baptism, self-denial, and service. As Paul writes in Galatians:

I have been crucified with Christ, and it is no longer I that live, but Christ living in me. That life which I now live in the flesh, I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me, and gave himself up for me (Galatians 2:20).

And there is a second, cosmic implication of this passage. Paul begins with comforting words about suffering. I have thought and said these words many times in dealing with faithful Christians who are facing intense suffering and sorrow:

For I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory which will be revealed toward us.

However, Paul also addresses the bigger picture. Salvation is not merely about personal, individual salvation — salvation also applies to all creation! Creation suffered because of the fall of humanity — nature itself was subjected to the bondage of decay. And, like a woman groaning in childbirth, nature itself groans and travails in pain.

When Jesus speaks of the tribulations and travails that prepare the way for the coming of the end of the age, he speaks of wars and rumors of wars and famines, plagues, and earthquakes (cf. Matthew 24:6-7) — and he cautions that these are not the signs of the end. And he says:

But all these things are the beginning of birth pains (Matthew 24:8).

In many ways, the argument that all creation has been subjected to the bondage to decay is a helpful understanding of theodicy, which addresses the theological problems of God’s omnipotence and goodness in the face of the existence of evil. This view provides a possible explanation of the existence of evil in creation — natural catastrophes, diseases, etc. They are not “permanent” aspects of creation — rather, like the birth pangs of a mother, they are temporary and transient and will be forgotten when the birth of the Kingdom of God is completed.

This also has implications for our Christian understanding of the natural environment and ecology. Creation is suffering, and also causes suffering — but creation itself is eager to see the fulfillment of God’s plan for all things:

For the creation waits with eager expectation for the children of God to be revealed. For the creation was subjected to vanity, not of its own will, but because of him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself also will be delivered from the bondage of decay into the liberty of the glory of the children of God.

God’s salvation is systemic. God saves and restores not only individuals but all creation as well.

RESPOND:

When we sing the old hymn “Blessed Assurance” by the blind composer Fanny Crosby (1801-1900), we are singing the theology of Romans 8:14-17 and Galatians 4:4-7 — the witness of the Spirit with our spirits that we are children of God:

Blessed assurance, Jesus is mine!

O what a foretaste of glory divine!

Heir of salvation, purchase of God,

Born of His Spirit, washed in His blood.

This experience is common to those who have made a decision to follow Jesus — people like John Wesley, who testified to a “heart strangely warmed” at a religious meeting on Aldersgate Street on May 24, 1738.

And people like Blaise Pascal, the French philosopher and mathematician whose heart was flooded with the light of Christ after a traumatic event in his life, on November 23, 1654. He sewed a piece of parchment into the lining of his coat from that time on with these words:

God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob, not of the philosophers and scholars… Joy, joy, joy, tears of joy… ‘This is life eternal that they might know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom you have sent.’ Jesus Christ. Jesus Christ… May I not fall from him forever… I will not forget your word. Amen.

That we can be adopted as children of God for the sake of Jesus Christ is amazing. That the Spirit of God whispers to our spirits that we are his children, and that we are entitled to call God Abba, Father is incredibly comforting. The entire Godhead of the Trinity is involved in bringing us into relationship with God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Lord, thank you that we are adopted as your children, and that you have made us your heirs. And most of all that we are able to cry out to you “Abba! Father!” Amen.

PHOTOS:

"Hold me Daddy" by Matthew Miller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license.

START WITH SCRIPTURE:

START WITH SCRIPTURE: